Architect, benchmark and the abandonment of ordinary language

The 13th instalment of Words of the Week, with some help from Keats and Nietzsche

Architect

Daniel Libeskind is an architect. When he is at work he thinks, draws, designs. He does not architect. That is not to say that the word does not exist. Any word that gets used exists, by definition. Indeed, the Oxford English Dictionary provides citations to this effect as far back as 1813. Keats wrote in a letter that “this was architected thus by the great Oceanus”. Yet here the sense is figurative and transformative. It is not a straightforward description of a computer design. So unless you are referring to something that the great Oceanus might have architected it is probably better avoided. There is no need to architect a schedule for a meeting: I doubt the great Oceanus had much time for meetings.

Benchmark

This is another example of a term that was once vivid and visual. For the builders of Greece and Rome a benchmark denoted a series of broad marks in the shape of an arrow that were carved vertically into stone. A horizontal cut would be made in the stone and an angle iron inserted to create a “bench” which would be used for site surveyors to assess the site. The benchmark was originally the vantage point from a judgment was made, rather than the measure of the judgment itself. Note how a tired word like benchmark has been revived by recuperating its visual image. This is a good example of the vitality of pictorial language.

The abandonment of ordinary language

The abandonment of ordinary language is damaging and dangerous. Where the language of business avoids ordinary discourse, crimes and misdemeanours are easier. Jargon can make wrongdoing sound innocuous. In 2008 the complex mathematics of highly geared financial packages exceeded the capacity both of regulators to set appropriate guidelines and of most practitioners to understand the risks. If the language of sub-prime had not been so clogged with technical jargon, the world might have been alerted to the fact that a disaster was about to unfold.

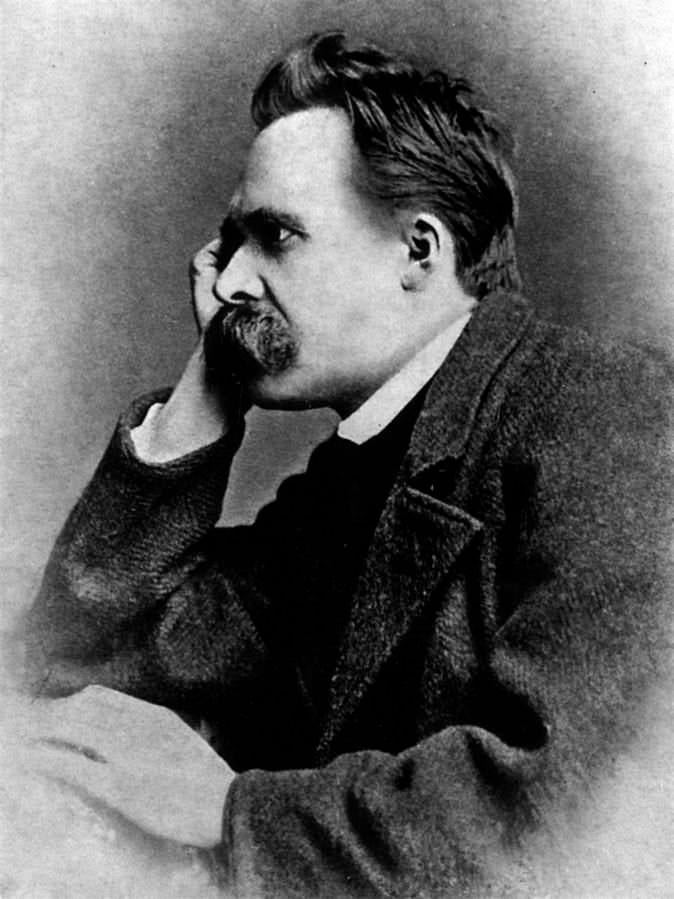

Friedrich Nietzsche saw all this coming in On Truth and Lies in an Non-Moral Sense, published in 1873, in which he wrote of the “mobile army of metaphors…. which are worn out and without sensuous power; coins which have lost their pictures and now matter only as metal, no longer as coins”. Every generation in business invents its own mobile army. You can speak the leveraged, value-added idiom of financial services. You can talk bandwidth off-line with the tech bores. You can talk battles and frontlines with the disruptors. Or you can embrace the organic evolution and self-actualizing of the new age.

The detachment of business from the society in which it is hosted has acquitted its own vocabulary, in both the theory and practice of business. All of these new vocabularies take ostentatious relish in how little they sound like ordinary life. Their mobile army of metaphors are dead on arrival. They fail the test of clarity. Business executives are damaging their own character with every utterance and yet there is surprisingly little tuition on offer. Remarkably, for a subject in which the skill of persuasion is paramount, the business school curricula offer no serious guidance on how to communicate. They disseminate a private language but they do not see fit to analyse it. The language of business is simply taken for granted as the appropriate way to speak.