Commas, jargon and going forward

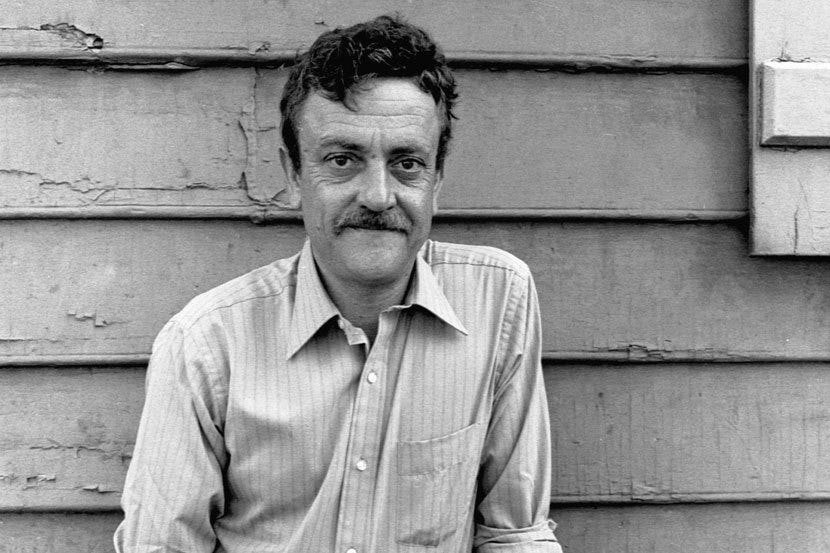

The seventh instalment of Words of the Week delivers writing advice via Chaucer and Kurt Vonnegut

Commas

The best way to work out if a comma is needed is to read the sentence out loud. When you run out of breath you need a break. Keith Waterhouse put it well: “it is not the function of the comma to help a wheezing sentence get its breath back.” Either a comma is required to separate the clauses in a single sentence and allow a pause, or a full stop is needed. Use commas in lists too, to separate items. Apart from that, be sparing because punctuation impedes the flow of a sentence. Stephen Pinker has a full treatment of the conventions of using commas well and badly in The Sense of Style. The most common injudicious usage in business writing is known as the “splice” which is the use of a comma to link two thoughts which ought to be separate sentences: “Our strategy is clear, we are trying to rent deckchairs on the beach for three quid an hour”.

Jargon

Jargon goes back at least as far as Chaucer. It originally referred to the inarticulate twittering and chattering of birds. In The Merchant’s Tale, Chaucer gives us an extended description of the wedding night of a particularly prolific knight called January, and his bride May. The fun goes on all night long and then, as day is breaking, January sits up in bed and says “and full of jargon as a flekked pye [magpie]”, which just means that he goes on a lot, not making all that much sense.

That much of Chaucer’s lost meaning has remained because this truly is the golden age of meaningless jargon. Its attraction in business is its capacity to make us feel exalted: needlessly complex language is a counterfeit signal of expertise. It conveniently erases conflict, because when nothing is being said there can be no disagreement. Jargon elevates routine processes and invests them with the fake glamour of obscurity.

Genuine fields of scholarship, such as epidemiology or inorganic chemistry, have technical vocabularies for which there are no colloquial alternatives. Jargon, by contrast, is the deliberate translation of ordinary ideas into complicated word patterns in order to exclude the uninitiated.

Business associates mimic their seniors to show that they belong. It makes a low art form sound like the highest science. But business is not a science. A business involves a complex array of human interactions. It is part history, part sociology and part anthropology. It is a realm not of scientific proof but of rhetorical proof.

Avoiding jargon is a cardinal obligation of good business writing. The philologist Wilson Follett called jargon “mere plugs for the holes in one’s thought.” A murky piece of writing is always the tip-off that a company is not clear on what it is doing. The best business writing is clear, precise and meaningful.

A final tip for avoiding jargon. Write down on a large piece of paper, every word you might use at work that you would never dream of using at home. Then tear it up and never use any of those words again.

Going forward

Time only travels in one direction, as far as we know. There is a brilliant passage in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five in which time travels backwards, a conceit that Martin Amis borrows in Time’s Arrow to make a point about moral responsibility. In the world of business time travels forward as a matter of course and there is no need to remind us.

There is another way that George Guarini, the CEO of United Business Bank, might have said “the business model of banking will be tested going forward”. He could have just said the business model will be tested. The idea that he is talking about time to come is contained in his future tense. The word “will” has said “going forward” so that you don’t have to.