Content, takeaway and gendered language

Words of the Week will create a glossary of poor language usage.

Welcome to Words of the Week, a new series in which I will help you improve the most important professional skill: the ability to communicate persuasively.

Some extracts will be taken from my book, To Be Clear (2021), and others will respond to items in the news. Consider this a rallying cry for better writing as well as a non-definitive guide to how it might be done.

Content

These days every second person has the term “content” in their title. If you are not a Content Manager then you will be a Content Creator, Producer or Designer. Content is written, devised, translated, edited and overseen by Content Specialists and Content Executives. There are Content Builders, Distributors, Officers, and Coordinators. Getting vaguer and vaguer (jobs without real content) there are Content Moderators and Content Platform Creators. All overseen by the Head of Content. Maybe a feudal hierarchy should be established. Baron Content. The Count of Content.

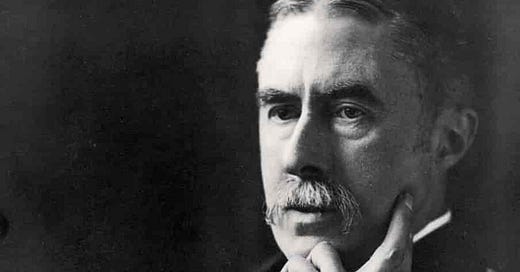

In A Shropshire Lad, his signature poem, AE Housman writes “Into my heart an air that kills/ From you far country blows/ What are those blue-remembered hills? What spires, what farms are those?/ That is the land of lost content….” Unless you are quoting Housman, which is laudable but unlikely, try not to use the word content. It is a fashionable vagueness which tries to cover everything from internal memoranda to television programmes. You might say that it has lost all content.

Takeaway

Best reserved for food taken out in a box. It is a good practice to try to crystallize what you have taken from a meeting but a good speaker will have done that refining and editing for you. So don’t suppose as a matter of course that there is only one thing to be taken from every address. Maxine Williams, the chief diversity officer of Facebook said that “the biggest takeaway is that the later you start, the harder it is”. Imagine if the great aphorists had ruined their pithy thoughts so efficiently. Oscar Wilde might have said that the takeaway here is that I have nothing to declare except my genius. The Duc de la Rochrefoucauld could have said that the takeaway is that our vices and our virtues are the same thing. How silly they were not to realize that their maxims could be so easily improved.

Gendered Language

The United States Declaration of Independence states that “all men are created equal”. It ought to be read with the assumption that the word men refers also to women but that is not to say that we should copy the practice. To refer to a professional position invariably as “he” is wrong. Not grammatically wrong but socially and morally wrong. The codes of language often erase people from consideration and so it is wise, as well as common courtesy, to be sensitive to this fact. Most gendered terms have acceptable neutral alternatives (man/person; mankind/humanity, policeman/police officer and so on). The thorniest issues may arise over the use of the gender pronouns. This is less of a problem in English than it is in languages in which words are either preceded by a gendered preposition (la vie en rose) or take a gendered ending (Latino) but it still matters. It is lazy to use “he” when not all people referred to are male. Using “he or she” is reasonable, although a bit cumbersome. Some writers alternate genders at random although that is a tactic that rather draws attention to itself. Perhaps the neatest solution is to use “they” as a singular pronoun. English does, as it happens, have a gender-neutral pronoun and it is not true, as the grammar purists often assert, that “they” is ungrammatical. It is, in fact, perfectly acceptable English.

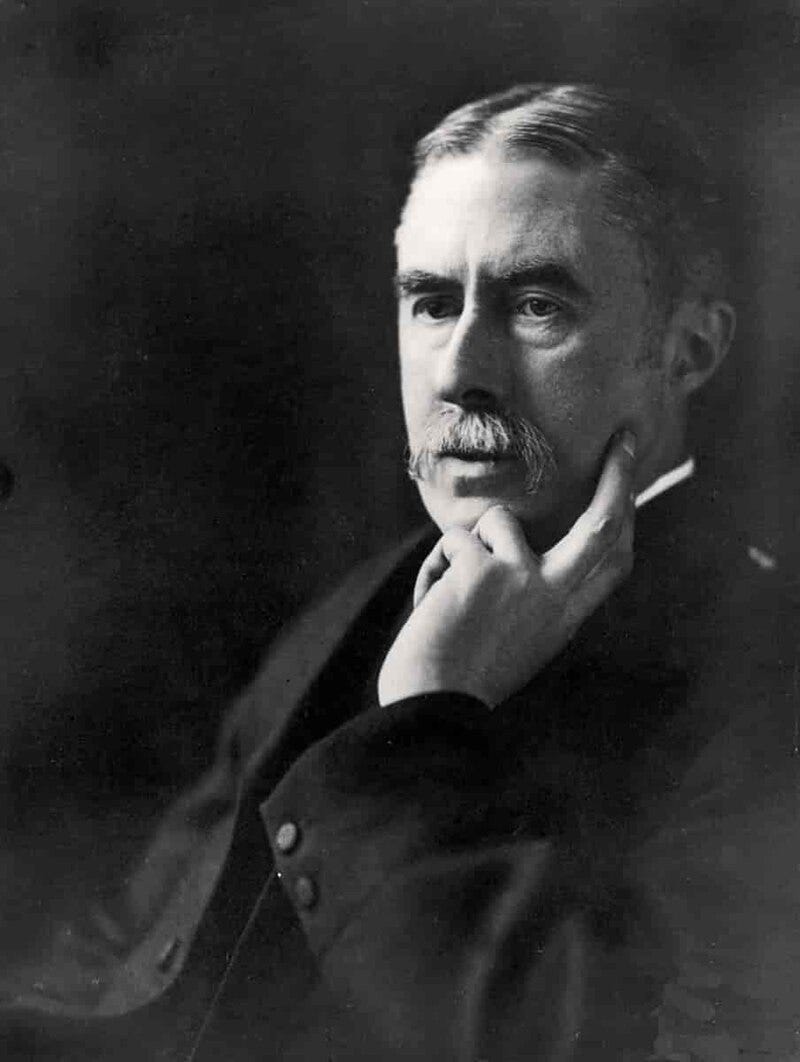

Constables from the Grammar Police may try to have you arrested but using “they” for “he or she” has a noble heritage. In the King James bible, the Gospel of Matthew has “If ye from your hearts forgive not every one their trespasses”. Chaucer and Shakespeare use the same locution. You can find it in Swift, Byron, Thackeray, Wharton, Shaw and Auden. Jane Austen, who used “they” regularly, writes in Mansfield Park “I would have everybody marry if they can do it properly”. Indeed, the use of “they” and their” was standard English in the Victorian era. A celebrated recent usage, which attracted the scorn of the grammar police, came from Barack Obama. In a press release in 2013 President Obama praised the decision of the Supreme Court to strike down a discriminatory law with the gender-neutral claim that “no American should ever live under a cloud of suspicion just because of what they look like”.

If, even with the endorsement of President Obama, you still feel uncomfortable with “they” or if the sentence really is about an individual which makes the use of “they” seem strange or impersonal, there are a couple of tricks that avoid the issue. Instead of writing “every banker deserves their bonus” you could say instead “all bankers deserve their bonus” or you can make the sentence more generic by saying “all bankers deserve a bonus”. (Never mind for the moment that it’s not true). But there is no special need to use either of these tricks. “They” really is fine.