Pretentious diction, neologisms and the passive voice

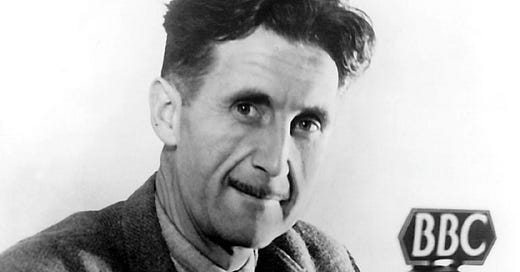

In the sixth instalment of Words of the Week, we discuss Orwell, Shakespeare and the perils of the passive voice

Pretentious diction

One of the blights lamented by Orwell is rife in modern corporate writing. The people at Toyota seem unaware of the useful and well-known word “car” which they call instead a “sustainable mobility solution”. Speedo claim to offer not a swimming cap but a “hair management system” and Nestle advertised an “affordable portable lifestyle beverage” known to the rest of us as a bottle of water.

This extends to pretentious claims about the world. WeWork, for example, stated as their aim the desire to “elevate the world’s consciousness” as if they were drafting a terrible rewrite of the preface to Hegel’s The Philosophy of Right. They provide office space and the world needs office space. There is something oddly insecure in these extravagant and bizarre claims. There is nothing wrong with saying you can use our good offices. There, they can have that slogan, if it’s not too late.

Neologism

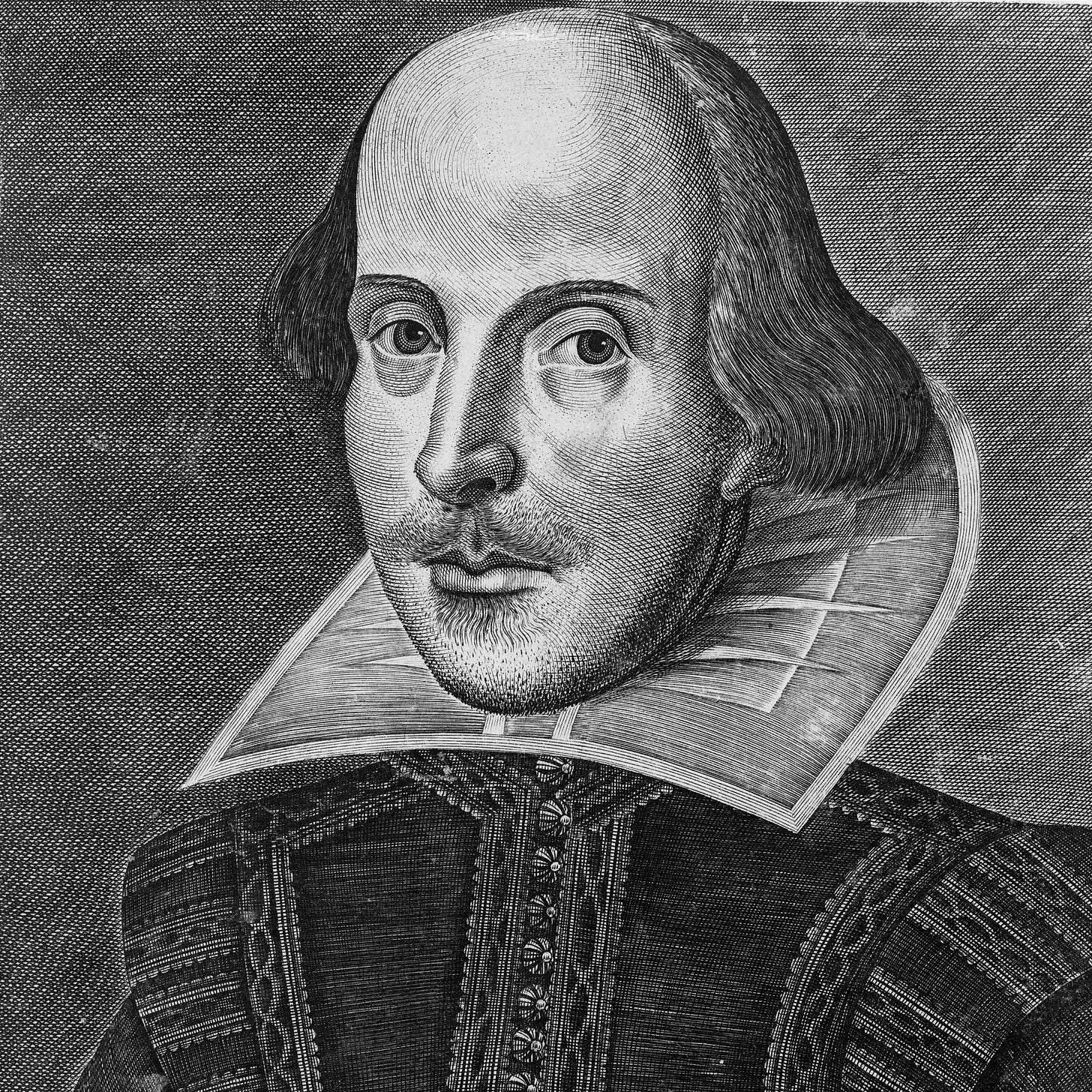

Eras of great tempest bring with them linguistic change as new terms are invented to describe novel circumstances. Shakespeare was a notable coiner of new words. Among those words we still use, Shakespeare was probably the first source for accessible, accommodation, addiction, barefaced, champion, characterless, circumstantial, compromise, control, countless, critical, defeat, domineering, employment, engagement, excitement, foul-mouthed, frugal, generous, ill-tempered, import, investment, lacklustre, lament, manager, marketable, money’s worth, negotiate, overpay, overview, profitless, retirement, subcontract, successful, supervise, title page, undervalue, unlicensed, unsolicited, valueless and watchdog.

Writing well about business would be a lot more difficult if we forswore use of all those. But just to show that language is alive there are also some Shakespearean inventions that we have killed off. We no longer have much use for bodikins, braggartism, brisky, broomstaff, budger, coppernose, fangled, flirt-gill, keech, kickie-wickie, lewdster, plumpy, skimble-skamble or wittolly. The point is that every new coinage should be judged on its merits, not disdained, or even embraced, simply because it is a novelty.

Not every neologism adds to the rich expressiveness of the language, though plenty do. One coinage we might like to revive, for example, is fat-witted.

Passive voice

It is often said, with no real justification, that nouns should not be verbed. Far more common, in fact, and much more insidious, is the habit of turning verbs into nouns. As soon as you write “there is no expectation that” rather than “I do not expect” you are evading responsibility for the thought. The scholar of the written word Helen Sword calls these constructions “zombie nouns” because nobody is doing the expecting; it just seems to happen. The passive voice always allows you to pretend that you did nothing. It wasn’t your fault. Mistakes were made. Just not by me.